NASA Project Studies How Urban Centers May Trap Birds During Migration

March 4, 2021 - Diane Huhn

For many of the world's birds, the most dangerous time in their lives occurs during their annual spring and fall migrations. For some, migration may mean a several hundred-mile trip from a sub-tropical island in the Bahamas to a young Jack pine forest in northern Michigan. For others, such as the Arctic Tern, it may be a dizzying journey of more than 55,000 miles from pole to pole each year. Due to ecological requirements for breeding, some species' very survival depends on their ability to arrive at these highly specialized habitats.  That trip is also dependent on locating suitable patches of habitat along the way that provide the critical food and safety they need to rest and refuel before continuing the journey. Some of these habitat patches can lie smack dab in the middle of cities, and recent work suggests that cities might actually be attracting birds into these more dangerous stopover locations.

That trip is also dependent on locating suitable patches of habitat along the way that provide the critical food and safety they need to rest and refuel before continuing the journey. Some of these habitat patches can lie smack dab in the middle of cities, and recent work suggests that cities might actually be attracting birds into these more dangerous stopover locations.

For centuries, human populations have been shifting toward urban centers and, of course, have been altering the landscape of natural communities in the process. Understanding the scope and impact of urban development on such communities is pivotal to the intentional conservation of the biodiversity birds require. Scientists such as Michigan State University's (MSU) Geoff Henebry and Kyle Horton of Colorado State University (CSU) are studying how cities influence and disrupt avian migration patterns by bringing together sophisticated sensors and datastreams, including multiple National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) products with analysis of in-situ weather radar data and community science observations collected from eBird. Managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, eBird is one of the world's largest biodiversity-related science projects, with more than 100 million bird sightings contributed annually by birders and nature enthusiasts from around the world. By harnessing the advanced computational power provided by the Institute for Cyber-Enabled Research (ICER) at MSU, the pair are working to understand how some migratory birds get "trapped" by the creature comforts that certain urban habitats can provide.

Specifically, the two are teaming up through a $780,000 grant funded by NASA's Biological Diversity program to explore how urban areas affect the spring and fall migration dynamics along the Central Flyway. Within the US, the Central Flyway generally spans Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, and the eastern portions of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Horton is the Principal Investigator for the project. He is an Assistant Professor at CSU in the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology. His research focuses on aeroecology, the study of bird, bat, and insect migration using the national network of weather radar stations. By removing the precipitation signals from the radar imagery, Horton's lab can track the movement of migrating birds as they take off near dusk and land near dawn.

Horton is the Principal Investigator for the project. He is an Assistant Professor at CSU in the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology. His research focuses on aeroecology, the study of bird, bat, and insect migration using the national network of weather radar stations. By removing the precipitation signals from the radar imagery, Horton's lab can track the movement of migrating birds as they take off near dusk and land near dawn.

Henebry is a Professor in the Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences and the Center for Global Change and Earth Observations at MSU. As Co-Investigator on the project, Henebry brings years of experience working with diverse types of remote sensing data to characterize pattern and change in the land surface. After seeing a presentation on aeroecology given by Horton at a workshop in the summer of 2019 at the University of Oklahoma, Henebry asked if Horton would be interested in collaborating on a proposal to the NASA biodiversity program.

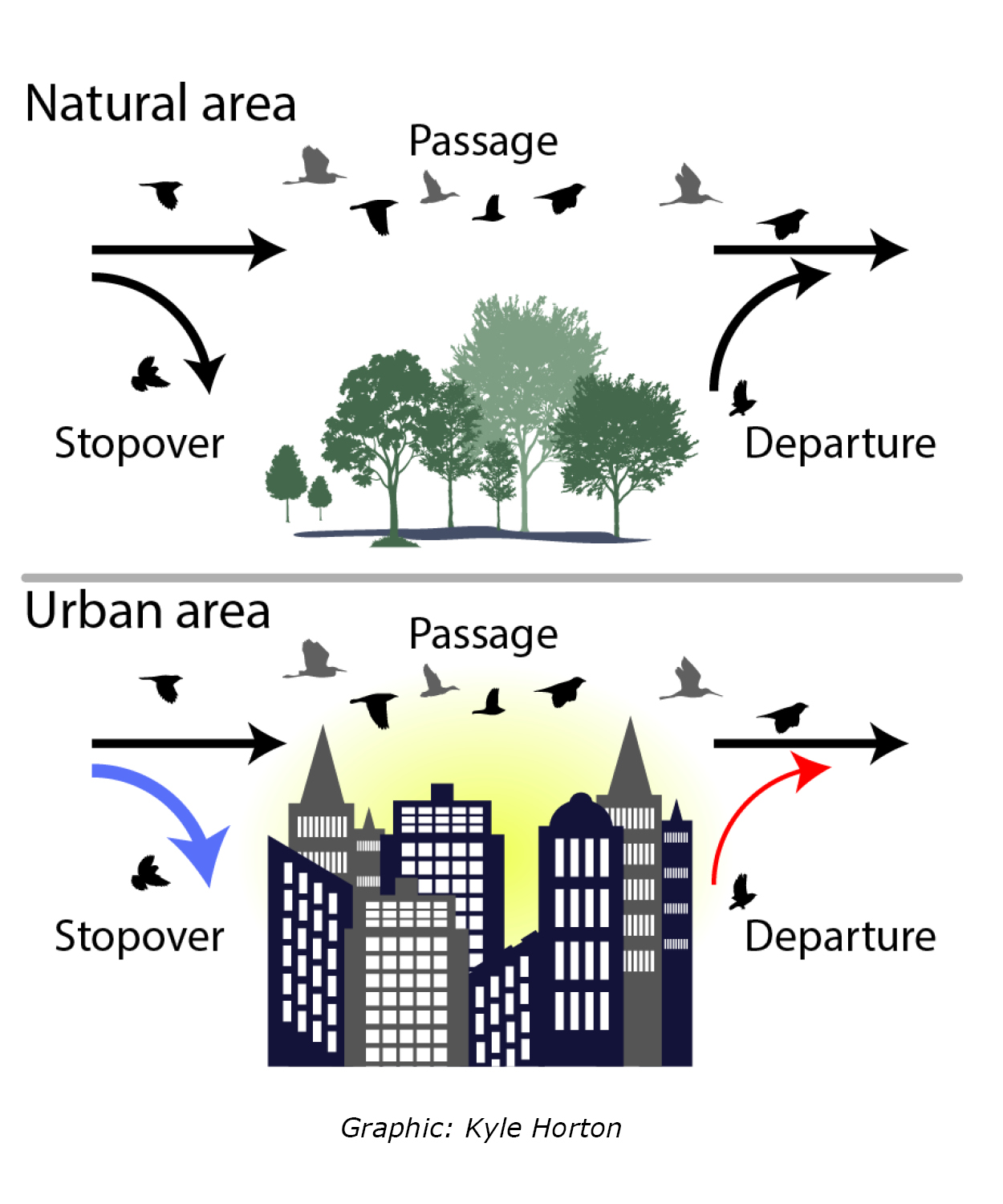

It has long been known that the northward spring migration season is paced by snow and ice melt combined with the greening of vegetation, and the fall is paced by the onset of colder temperatures and the seasonal browning of plant matter. However, by trapping some of the heat produced through human activity and human-made infrastructure, urban areas often act as heat islands relative to nearby rural areas. Horton and Henebry hypothesize that since urban areas can form oases of warmth, food, and shelter, they can actually disrupt the pace of migration. Urban light pollution can also impact migratory birds since most species migrate during the nighttime. Previous studies have shown that these birds are attracted to urban lighting. The combination of these factors has led the team to consider urban trees and parks as potential ecological traps.

A male Scarlet Tanager forages in a suburban park during its annual spring migration. Twice a year, this long-distance migrant flies across the Gulf of Mexico between its breeding grounds in eastern North America to its wintering grounds in South America. For a successful journey, such birds depend on patches of stopover habitat to provide adequate food, rest, and shelter along the way.

Timing of the migrations can be a life-or-death matter for migratory birds. While the juvenile Baltimore Oriole attracted by light pollution to a Midwestern city during migration may be able to temporarily seek refuge and food no longer available in its birthplace, if it lingers too long, it may never make it to its wintering grounds in Costa Rica. This situation can occur because the additional food sources it will need along the way may no longer be available if the journey extends too late in the season. With urban areas expected to grow for the foreseeable future, it is important to gain continental-scale insights now, rather than when it is too late. Understanding these processes can give us the time to develop plans and strategies necessary to ensure a continued co-existence with our feathered friends.

For additional information regarding this project, please click here.