AGRICULTURE: EARLY BEGINNINGS

When pioneers from the East first encountered patches of treeless prairie lands in Ohio

they assumed that the absence of trees was a sign of poor soils. They soon discovered that

this was not at all the case, and although the absence of timber for building and heating

purposes continued to be a deterrent to the rapid settlement of the vast prairies of

Illinois, settlers in Michigan quickly gravitated to the small prairies scattered

throughout southwestern Michigan. At these sites, timber was readily available in the

vicinity, where wide, magnificent oaks stood scattered in oak openings. One advantage of

the prairie lands was that the pioneer did not have to engage in the backbreaking task of

clearing the trees from the land, although it was very difficult to break up the soil, the

task often requiring several yoke of oxen. Grass on the prairies grew waist-high, and

naturally the root growth was thick and deep. But the soil, once made cultivable, was

fabulously rich. The settlers were also attracted to "oak openings." Here the

oak trees grew so tall and shaded the ground so completely that little or no brush or

other vegetation grew underneath. It was possible to drive an ox team through oak openings

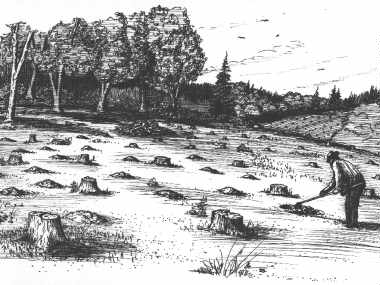

for miles along an unblazed trail.After the land was cleared of trees by the lumberjacks,

areas viewed as profitable for agriculture were cleared of stumps and early agriculture

began. The image below shows an early settler planting potatoes between stumps.

Source: Unknown

However, farming on an extensive scale developed slowly in Michigan. Until 1818 it was not

possible to obtain legal title to any land in Michigan except for small areas in the

immediate vicinity of the two principal settlements: Detroit and Mackinac. There were

"squatters," of course---pioneers who helped themselves to land in the

expectation that when the government placed it on the market their rights to ownership

would be accepted. These pioneers took a risk when they invested their time and labor in

the improvement of land that was not their property, but sometimes it did pay off and they

got the land.

Click here for full size image (264 kb)

Source: Unknown

Before settlers could legally obtain any land, the government

first had to persuade the Indian tribes to relinquish their claims to the land. To the

American pioneer, the Indian had no positive effect on the economy. As the fur trade

declined and agriculture took its place as the mainstay of Michigan’s economy, the

Indian became a barrier to the exploitation of the area’s land resources. What the

Michigan pioneers wanted was the Indian’s land; what became of the Indians was of no

concern to them.

Lumber companies had no desire to own already logged parcels of land and thus found

themselves trying to sell large tracts of land in the 1880s and 1890s. They vigorously

promoted the former forests as good farmland, ready for the plow, but experience soon

proved that this was not the case. Most of the land simply could not support continuous

farming, and its fertility was soon exhausted. Families that had put all their savings and

hopes into such a farm often had no alternative but to give it up when they could not pay

their taxes. Tax delinquent land as well as acreage simply abandoned by lumber companies

was thus acquired by the State of Michigan, forming the basis for its early efforts toward

reforestation and land management.

Thus, Michigan’s lumber boom provided many settlers with cutover

lands to farm, a ready market for their products and winter employment.

Source: Unknown

As one example, by the turn of the century, Kalkaska County had 782 farms totaling 33,641

improved acres. Potatoes were one of the county’s major crops. Apples were also

important. In 1904 over 21,000 trees were harvested in Kalkaska.

Work on 19th century farms was tied to the seasons. The farm

year began in April when the land was dry enough to start plowing. Because plowing was so

difficult on newly cleared land still thick with stumps, crops were often planted on

ground that was merely harrowed or in holes dug among the stumps.

Source: Unknown

After a few years of planting in this manner, stumps and roots were sufficiently rotted to

be "grubbed out" and piled up.

Tripods like the one shown below were used extensively to pull out the large stumps and

prepare the land for cropping.

Source: Unknown

Piles of stumps were eventually burned.

Source: Unknown

Eventually whole fields were cleared and plows turned over thick ribbons of loamy soil.

With a horse- or oxen-drawn plow, a farmer could till about an acre a day.

Source: Unknown

Each spring the newly plowed fields had to be picked clean of stones

heaved up by the frost. With a certainty seldom enjoyed in more desirable crops, stones

reappeared every year. The stones were piled at intervals in the field, then hauled away

on a stoneboat---a heavy sled used on rough ground rather than on snow.

The fields were then harrowed (tilled). A large, horse-drawn rake (often called a

"drag"; see below) with heavy iron or wooden teeth, the harrow was dragged over

the plowed land to break up and smooth the loosened earth. Harrowing also turned up roots,

which had to be picked from the fields. Often, either in the spring or the fall, manure

was spread on the fields for fertilizer and tilled into the ground.

Source: Unknown

Planting followed harrowing. Many pioneer farmers "broadcast"

their grain seed (as opposed to sowing it in discrete rows). Clover and oats were sown

first, since they could survive late frosts. Wheat was planted next, followed by potatoes

and corn in mid to late May.

Harvesting began in July with haying. Hay was cut with a scythe

(below).

Source: Unknown

The process required skill, balance and a sense of timing. Work began at daybreak. The

reaper moved slowly through the hay, rhythmically swinging the scythe. The hay was allowed

to dry for a day or two, then raked into shocks (small piles) to dry further if the

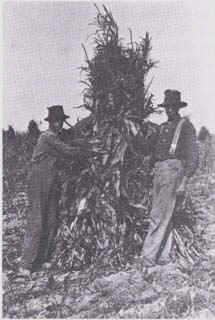

weather was good. (The image below is of a corn shock, but hay shocks were not much

different.)

Source: Unknown

It was then pitched onto a wagon and taken to the barnyard. To keep it outdoors, which was

necessary if the family did not have a barn, it was stacked carefully around a pole and

covered it with straw to shed rain.

Oats and wheat were harvested next with a grain cradle. The cradle was similar to the

scythe except that it had several long fingers of wood projecting from the handle,

parallel to the blade. These caught the grain as it was cut, allowing it to be laid gently

on the ground so that the seeds did not burst from the heads. The cradler proceeded much

as the hay reaper had, laying down neat swaths of grain and being careful to avoid leaving

"candles," as tall stubbles were called. Behind the cradler came a workman

raking and binding the freshly cut grain into sheaves about a foot in diameter. With one

person cradling and one binding, two people could harvest about two acres per day. The

sheaves were placed in shocks and allowed to stand two or three weeks for further drying.

Source: Unknown

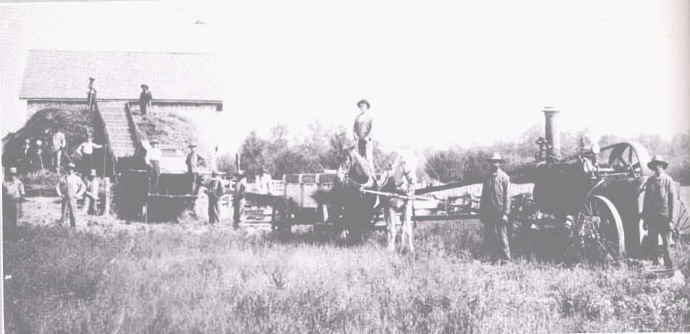

Upon drying, the grain was threshed, wherein the grain was separated from the straw.

Threshing was a large endeavor, in which several families participated. The

threshing machine was moved from farm to farm, until everyone's grain had been

"separated".

Source: Unknown

Unlike other grains, corn could be harvested over a long period, as ears ripened at

different stages before the stalks were cut in September. One man could cut about 1/2 acre

per day. The farmer bound an armful of stalks and placed the bundles in shocks. The shocks

stood in the field through the fall until the corn was husked late in the season. On farms

with inadequate shelter for hay and fodder, corn was often husked in the field. The stalks

and the shocks were brought in as needed for fodder during the winter.

Potatoes were ready for harvesting in September. They were dug with a

hand hoe or potato hook and left on the ground briefly to dry. When they were gathered

later, the dried earth crumbled off leaving the skins clean and the potatoes ready for

storage.

Threshing followed harvesting. Grain was spread in a shallow layer on

hard, dry ground, then beaten with a flail to separate the seeds from the heads. The flail

consisted of two short, thick poles connected by a leather thong strung through a hole in

one end of each pole. A helper swept up the threshed grain, including much of the chaff

that had settled, and bagged it for storage until winnowing. Threshing was dusty, hard

work and dangerous if one were not skilled in controlling the flail. An average worker

could thresh 7 bushels of wheat or 18 bushels of oats daily.

The threshed grain was cleaned with a winnowing fan, a rimmed half-disk

made of tightly woven splint. A peck of grain was placed on the splint surface, the rimmed

edge of the fan was placed against one’s torso and the fan was swept up and down,

tossing the grain in the air. The grain fell back on the fan while most of the lighter

chaff and dust floated to the ground. This, too, was dusty work and not highly effective

in obtaining quality seed or clean grain for milling. The winnowed grain was bagged or

spread in shallow trays for storage, and the chaff was swept up and saved for poultry

food.

In winter many farmers turned to working in the woods. Many hired out

their horse "teams" to logging operators, while others worked to clear more of

their own land and sometimes to supplement the family income. Logging started in early

December and continued until the maple sap began running in late winter. Cordwood for the

next year’s fuel supply was cut, and any surplus beyond household needs was sold for

one dollar a cord-delivered. Timber for fencing was cut, split and allowed to season for

at least a year. Sawlogs for lumber were cut, hauled and piled for use on the farm or sold

to the nearest mill.

Late winter brought syrup making---the busiest activity of the year.

Syrup making usually started in March, when warm days and freezing nights made the sap

rise. The season was brief, but while it lasted the work went on around the clock. Before

the sap started running, the family cleaned the various implements, swept out the

sugarhouse and stacked a dozen cords of wood nearby. A spout was tapped into each maple

tree. The sap flowed through it into a trough or bucket hanging below. The sap was then

emptied into barrels, which were taken to the sugarhouse and emptied into a big iron

kettle. The kettle was suspended over a fire hot enough to maintain the sap at a boil. A

chunk of fat in the kettle kept the sap from boiling over and imparted an oily texture to

the finished product. After several hours of boiling down to a thick syrup, the amber

liquid was tested to see whether it had reached the sugar stage. If it had, the fire was

extinguished and the syrup stirred until it became granular.

With the end of the syrup-making season, the farm year was completed

and the cycle was ready to begin anew.

The abandonment of farm lands

The early 20th century's demise of lumbering coincided with a marked decline in farming in the sandy northern counties of Michigan. As farmers throughout the northern Lower Peninsula discovered, the soils of the cutover lands soon lost their fertility.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.